THE SCHIZOPHRENIC MEMORY OF

CHINATOWN, MANHATTAN

NAAB Bachelor of Architecture Thesis

May 2013

The Schizophrenic Experience

Current practice of historic preservation in the United States maintains Schizophrenic behaviors, as it emphasizes the preservation of the facade. By institutionalizing preservation, a framework establishes relationships between signifiers [the facade] and the signified, or the memory of a space. By the act of imitation, the preservation of the facade fabricates a national narrative built by fragmented memory, characteristic of the Schizophrenic Experience. In turn, a narrative built by facades becomes a socio/political instrument establishing a fabricated memory for the collective consciousness. The society saturated with images is one used for the commercialization of heritage; reified images created by the lack of historical continuity perpetrate the necessity for consumerism at large.

The Schizophrenic Narrative is Reified

In his article entitled, "Postmodernism and Consumer Society," Fredric Jameson describes Schizophrenia not as a diagnosis, but rather, characteristic of a postmodern society. Schizophrenia is the inability to develop a notion of identity by lack of language acquisition. Jameson claims that isolation of individual signifiers enables each [signifier] to be reified, or becoming more of an "image" Jameson's understanding of the Schizophrenic Experience is one of"isolated, disconnected, discontinuous material signifiers that fail to link up into a coherent sequence." He claims that because the signifier is isolated, it becomes more literal.

Due to lack of historical continuity, the Schizophrenic fails to fully acquire language, and as a result, cannot define oneself over a period of time. Jameson understands that temporality is an effect of language, and the meaning of a signifier comes by inter-relationship of the material signifiers in a coherent sequence. The Schizophrenic Experience is to define oneself in the perpetual present by claiming identity in a signifier imitating the immediate reality. By claiming identity in the perpetual present, the Schizophrenic is denied the formation of ego.

Jameson's proposed treatment for the Schizophrenic imposes the Oedipal cycle, defined by Jacques Lacan to be characteristic of the normal ego development. To create historical continuity, and to solve the issue of claiming the perpetual present as 'self,' Jameson proposes a pattern of signifiers to suggest a notion of ego. Jameson proposes a complete narrative created by use of pattern; and thus, the narrative lends itself to suggest the comprehension of ego formation.

If the Schizophrenic claims the immediate reality to define "I" and "me," then by contrast, the Oedipal cycle allows the Schizophrenic to seek ego formation by suggesting historical continuity found in narrative.

Yet, critics say imposing a complete narrative for the Schizophrenic, maintains the same dilemma as the Schizophrenic seeking ego in individual signifiers when the narrative maintains same characteristics as the signifier. The reified narrative is equal to an isolated signifier. Because the narrative represents something else besides itself through the act of imitation, it proposes similar characteristics to an autonomous signifier. By the process of reification, the perpetual present becomes an image because the narrative imitates historical continuity found in memory.

The Imposed Narrative by Institutionalizing Preservation

2013, steel, reflective plexi glass, 36 x 36 ins

Like the Oedipus treatment of the Schizophrenic, a narrative of nostalgia is established by the preservation of facades through institutionalizing historic preservation in the United States. A relationship to the past -- both individually and collectively -- cannot be realized due to time, and therefore the Historic Preservation Standards created at a federal level, establishes a narrative for the nation. In turn, with the institutionalization of preservation, various heritage places in Modern America have been preserved as mere images of the past.

2013, "carrying the reflective cross thru chinatown" film still

Landmarked neighborhoods serve as an archive of images serving as memories. Thus, the memory of the city is largely dependent on images alone to construct a narrative. With historic neighborhoods and buildings preserved nationwide by Standards emphasizing faciality, only a small narrative of the history of the United States is rehabilitated, reconstructed, and preserved. Most buildings protected by the Standards were erected by [and only represent the narrative of a minority of the inhabitants of the cities in which the facades represent. The limited narrative is constructed by the preservation of facades.

If Jameson claims that the isolation of individual signifiers enables each [signifier] to be reified, becoming more of an "image," then preserving only the facades of historic structures alone will lead to "isolated, disconnected, discontinuous material signifiers that fail to link up into a coherent sequence." By preserving the façade, the signifier of history becomes isolated, and it becomes more literal. The facades in-turn create a commercialization of heritage.

The Forward Building as Analogous to Chinatown, Manhattan

The Schizophrenic Memory of Chinatown depicts a narrative founded in images as well as the commercialization of heritage. Although Chinatown remains one of the last areas designated as a landmarked neighborhood in Manhattan, it maintains schizophrenic characteristics defined by Jameson.

Beginning in the in the late 1970s, Chinatown experienced an influx in foreign investments. Simultaneously, federal and state regulation served as a means to dissolve manufacturing jobs and perpetuate the rise of tourism in the ethnic enclave. Consequently, a narrative was established to depict Chinese heritage and culture by images that were easily recognizable by an outsider.

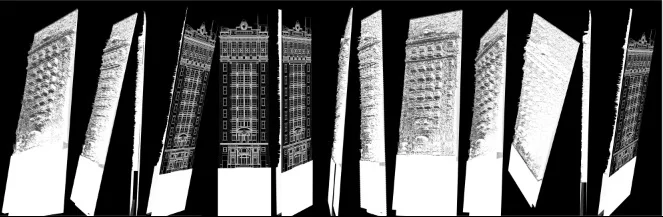

The Forward Building, located on East Canal and Broadway currently stands as a landmarked building, but furthermore, is analogous to Chinatown's Schizophrenic Memory. The facade of the building depicts social reform and labor, while the building serves as luxury condominiums.

Erected by the Socialist paper of the Yiddish neighborhood, the Forward Building has since become an isolated signifier due to a lack of memory retained in its immediate surroundings although it has been preserved by the Secretary of the Interior's Standards for Preservation. The facade of the Forward Building has in turn become an image, and a reified narrative unto itself surrounded by vast real estate capital foreign investments.

Embedded in the facade of the Forward Building are emblems of social reformation leaders, such as Karl Marx and Engels: these emblems serve as signifiers for labor and social equality, two ideals within the vocabulary of the immigrant Jewish neighborhood. The emblems thus act as multimodal objects, whose duality in function no longer suffices due to the disappearance of the Yiddish newspaper, of manufacturing jobs in Chinatown, and low to middle income housing.

Both landmarked buildings and new facades construct a narrative for the Chinatown identity in Manhattan; the narrative is created and preserved by images. Landmarked buildings of Chinatown no longer represent the history of the space, or the heritage in which they signify, but rather have become images unto themselves that are further perpetuated by standards of preservation and upheld by the commercialization of heritage.

Conclusion

When a building is designated as a historical landmark, the memory and integrity of the building is preserved by a facade, or an image of the original building. By institutionalizing preservation of landmarked buildings, a framework is established creating a Schizophrenic Experience of the built environment.

We defined the Schizophrenic Experience in three scales: 1) The built environment preserved in a postmodern society 2) Chinatown, as an ethnic and economic enclave enabling the Schizophrenic Experience, and 3) The Forward Building, a structure signifying Chinatown by way of analogy.

References

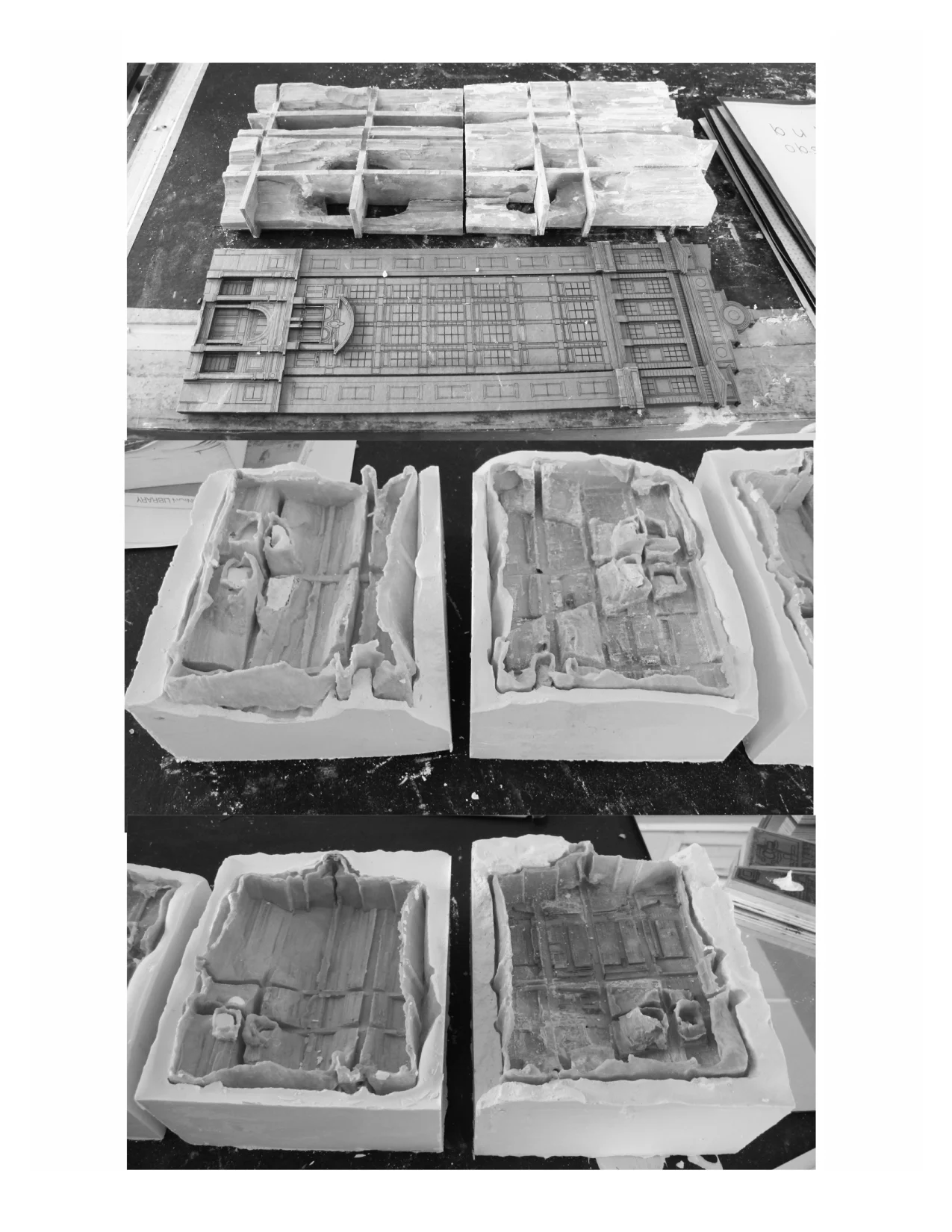

2013, plaster, bass wood, masonite, rubber

This article was initially written as part of a thesis for a Bachelor of Architecture at the Cooper Union from 2012-2013. It was accompanied by a series of models and a book. The schizophrenic tendency is to create identity within a fabricated language: thus, the thesis -- and the analogies used within the thesis -- are representation of the immediate surroundings in which the thesis was created.

The Forward Building in the thesis represents The Cooper Union: once a signifier for social reform, an institution for the education of the working class. Now, the Cooper Union is inhabited by the 1% and no longer stands as an emblem for labor, social reform, free thought, or free education, although the facade remains as such.

The Cooper Union Foundation Building also stands as a great example of the schizophrenic condition established by institutionalized preservation; it is a landmarked building. John Hejduk, Dean of the School of Architecture at the Cooper Union (1975-2000) completed a renovation of the building in 1974. The interior of the building was gutted and reconstructed; yet, the image of the facade was rehabilitated per federal standards. The rehabilitation and preservation of the facade masks the interior reconstruction, and in-turn, the memory of the Cooper Union remains fragmented, left to be reconstructed by those inhabiting the institution today.

“While Eve waited

Inside of Adam

She was his

Structure

Her volume

Filled him

His skin hung

On Eve’s form

When God

Released her

From Adam

Death rushed in

Preventing collapse”

Download a version of the Thesis Book Here:

https://drive.google.com/open?id=0ByzJKXbHuvWhT2tKVXpaVnVVWHVaNl91MnJJVTVnOFVFZkhV

Further Readings Online:

Jameson, Postmodernism and Consumer Society

Deleuze and Guattari, Anti-Oedipus

Edward Winters, Aesthetics and Architecture

Last Updated: 2017-02-02 12:39